London 1851- First International Chess Tournament

London 1851- First International Chess Tournament

The first international chess tournament took place in London May, 1851. The tournament, which was devised and organized by English chess champion Howard Staunton, was the first occasion that Europe’s greatest chess players came together in one place. Adolf Anderssen, the Germany school teacher took first place in the sixteen-player competition, giving him the title of world’s best player.

The Choice of the Greats

Ludwig Bledow offered in a letter (published in 1848) that he and von der Lasa conduct an international tournament in Trier (Germany) and the winner will be acknowledged as the world champion. However, Bledow died in 1846, and the letter was only published after his death. Staunton’s decision to arrange the London International event may have been influenced by this news as well.

The Great Exhibition of 1851 was held in London to display British industry and technology. There were now railways everywhere, and new ships had cut the travel to the Americas from a month to a week. London’s burgeoning chess community felt obligated to do something comparable for chess. Howard Staunton suggested, and then led, the organization of the first-ever international tournament to be held at the same time. He saw the Great Exhibition as an once-in-a-lifetime opportunity since the obstacles to worldwide participation would be considerably eliminated, such as making it simpler for participants to get passports and take time off from work, and he created the first international chess tournament of the history.

Captain Hugh Alexander Kennedy, one of the organizers and contestants of the tournament stated before the tournament began that the victor should be considered as “the World’s Chess Champion.” There is no evidence, however, that recognizing a global champion was a stated goal of the competition.

Rules & Regulations

Staunton and his colleagues set lofty goals for this tournament, including summoning a “Chess Parliament” to complete standardization of steps and other rules, as there were still minor national discrepancies and a few self-contradictions; standardize chess notation; and agree on time limits, since many participants were renowned for simply “out-sitting” opponents.

Staunton also recommended creating a compendium of what has been known regarding chess openings, ideally in the form of a table. Because he did not believe there would be enough time in a single “Chess Parliament” meeting to deal with this as well, he proposed additional congresses, some of which might include knowledgeable enthusiasts of below-top-class playing strength, as well as an evaluation process for dealing with controversial issues and possible mistakes in previous decisions.

The Committee & The Fund

The Duke of Marlborough led the Committee of Management, although Staunton served as its Secretary, and the majority of its members were members of Staunton’s chess club, St George’s.

The strong London Chess Club boycotted the competition due to disputes in British chess at the time, and George Walker utilized his Bell’s Life column to attempt to sabotage the tournament preparations. Despite these challenges, Staunton was able to gather £500 for prize fund, which was a significant amount in 1851 and would be worth almost £500,000 in 2022.

England’s Chess clubs and abroad were approached for subscriptions. The Café de la Régence in France collected money, while the Calcutta Chess Club in India gave £100, with two of its key officials, John Cochrane with T.C. Morton, making two of the four greatest individual donations. The tournament, which started on May 26, 1851, was timed to correspond with London’s Great Exhibition.

Players

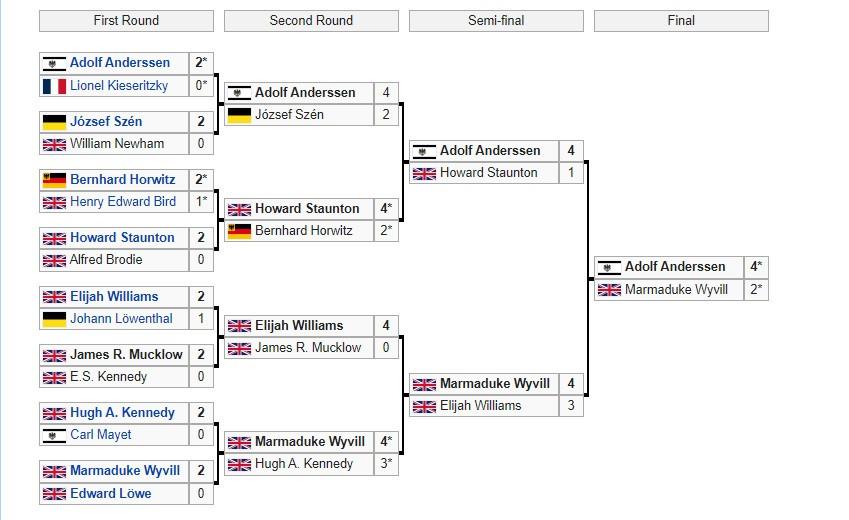

The competition was set up as a knockout tournament, with sixteen of Europe’s greatest players competing. Foreign masters József Szén, Vincent Grimm and Johann Löwenthal of Hungary; Bernhard Horwitz, Adolf Anderssen, Carl Mayet, and von der Lasa from Germany; Lionel Kieseritzky and Pierre Charles Fournier de Saint-Amant of France; and Alexander Petrov, Carl Jaenisch, and Ilya Shumov of Russia had all been invited. Howard Staunton, Marmaduke Wyvill, Elijah Williams, William Newham Henry Thomas Buckle, Captain Hugh Alexander Kennedy, and Henry Bird were the British players.

Unfortunately, many of those who were invited were unable to participate. Grimm was unlikely to attend due to his exile in Aleppo following his involvement in the 1848 Hungarian Revolution. Löwenthal had also taken part in the unsuccessful insurrection, but had escaped to America and established himself as a businessman. Löwenthal left his life behind in order to perform in London. Saint-Amant was unavailable since he had been sent to California as a diplomat by the French government.

Petrov and Von der Lasa were also unable to attend. Jaenisch and Shumov were unable to make it to the game in time. Buckle again failed to qualify for the event, and as the second-best British player after Staunton, he was the most important British player to lose out. Daniel Harrwitz was unable to compete due to a disagreement with the London Chess Club, which also decreased the pool of alternatives available, as George Walker, George Perigal, and George Webb Medley may have made for a better field if the boycott had not occurred. Anderssen was hesitant to accept his offer because of the trip expenses. However, if Anderssen did not win a tournament prize, Staunton volunteered to cover Anderssen’s trip costs out of his own money; Anderssen accepted this magnanimous offer.

Knock-Out!

The competition was set up as a single elimination tournament, with the eight losers from the first round being eliminated. Each match in the first round was a best-of-three series, with ties not counting. The next rounds were best-of-seven, with losers competing in consolation matches. The pairings were determined by random, since there was no seeding system like to that used in tennis events. Kieseritzky, Bird, and Löwenthal, three of the top players, all lost in the first round. J. R. Mucklow and E. S. Kennedy, two of the substitute players, were drawn one against another, and the winner (Mucklow) received a part of the prize money.

In the third-round semi-final, Anderssen defeated Staunton 4–1. Anderssen took first place in the fourth-round final, defeating Wyvill. Wyvill finished second in the event after a reasonably easy draw. Staunton finished fourth after a heartbreaking loss to Williams in the final round consolation match.

Staunton is often recognized as the best player in the world from 1843 until this event, thanks to his match win against Pierre Charles Fournier de Saint-Amant in 1843. Anderssen defeated Staunton throughout the event.

Anderssen is well known for his magnificent sacrificial attacking play in the “Immortal Game” (1851) and the “Evergreen Game” (1852), but few people are aware that he was also the undefeated winner of the first international chess competition!

Battle for A Place!

Staunton 3 – Williams 4 (1 draw) (For 3rd and 4th place)

Capt. Kennedy 0 – Szén 4 (1 draw) (For 5th and 6th place.)

Horwitz was victorious because Mucklow had defaulted (Match for 7th and 8th place)

Anderssen - World Champion of 1852

Despite the fact that some subsequent analysts thought the knockout system was problematic, Anderssen was regarded as a deserved winner. Staunton promptly invited Anderssen to a twenty-one-game contest for a £100 stake, as stipulated by the tournament regulations.

Anderssen consented to participate, but he was unable to do so straight away since he had been gone from Germany at his profession as a schoolteacher for more than two months. Staunton was also physically weak for an instant match. The contest that was supposed to take place was never held.

Anderssen was widely regarded as Europe’s top player as a consequence of his victory in this event, however he was never referred to as “world champion” as far as is known.

The concept of a global chess champion has been around since at least 1840, and first documented usage of the word “world champion” was in 1845, in Staunton’s Chess Players’ Chronicle, referring to Staunton. In the 1870s, Wilhelm Steinitz was commonly regarded as the “world champion,” but the first genuine world championship match was held in 1886 between Steinitz vs Johannes Zukertort.

Staunton published The Chess Event, a book about the tournament (1852). Although it was an outstanding account of the event, titled The Chess Tournament (1852). It was tainted by his lack of grace in accepting Anderssen’s triumph. Staunton attributed his bad performance to the stress of his tournament-organizing responsibilities, as well as a heart problem he had developed during a sickness in 1844.

During a break in the tournament, the legendary Immortal Game, Anderssen vs Kieseritzky, was played as an offhand game. It isn’t one of their first-round match’s games.

The London Chess Club, that had a falling out together with Staunton & his colleagues, arranged a tournament a month later that included a multi-national field of competitors (many of whom had participated in the international event), and the outcome was the same: Anderssen won. And, the rest is history!