Who was Bobby Fischer | Mad Chess Genius

Chess has crossed paths with several geniuses throughout its history. From Morphy in the 1800s to Carlsen in today’s era, the chess world feels like it has seen it all. With several reported IQ scores above 160, it’s no wonder that chess is the sport that comprises the greatest number of geniuses in any sport’s history. But even amongst geniuses, some stand out more than others.

If one were to ask for a top 10 list of the greatest chess geniuses, both alive and those who have passed away, it’d have to go something along the lines of the following: Paul Morphy, Jose Capablanca, Mikhail Botvinnik, Mikhail Tal, Bobby Fischer, Anatoly Karpov, Garry Kasparov, Vladimir Kramnik, Judit Polgar, Magnus Carlsen – and the reasons are known to many:

- Paul Morphy, the exceptionally gifted player who emerged at the top of the chess world at age 12.

- Jose Capablanca, the chess prodigy who picked up chess at 4 without being taught how to play and whose moves scored impressive overall accuracy according to today’s chess engines.

- Mikhail Botvinnik, often referred to as the Patriarch of the Soviet Chess School.

- Mikhail Tal, at the time the youngest world chess champion at 23 and probably the most eccentric one.

- Bobby Fischer… Let’s come back to this one!

- Anatoly Karpov, the player with the highest Elo performance ever recorded, and who played evenly with Kasparov.

- Garry Kasparov, the one who stayed at the top for 20 years and later Magnus’ coach.

- Vladimir Kramnik, multiple times World Champion and the only human being to have beaten Kasparov in a match.

- Judit Polgar, the woman who reigned women’s chess for decades and rated above 2500 at 12 years old.

- Magnus Carlsen, the chess prodigy who beat Karpov at 13 and first player to cross the 2850 mark (at 22!), set by Kasparov.

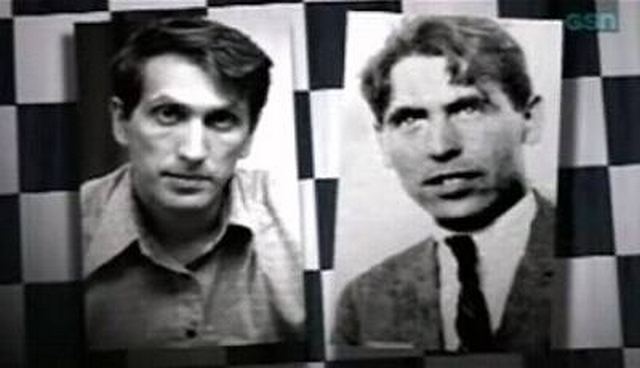

Who was Bobby Fischer?

Today, however, we’ll solely focus on Bobby Fischer. Robert James Fischer, most commonly known as Bobby Fischer, was without a doubt one of the greatest geniuses chess has come across. As he famously stated, “I’m not a chess genius. I’m simply a genius who happens to play chess.”. And guess what Bobby? We’re on your side.

Looking back, born in the United States in 1943, Fischer’s footprint was set to leave a mark. Nowadays, one can find compelling evidence that his biological father was Paul Nememyi – a physicist and child math prodigy who published a textbook on mechanics that was later studied by German undergrads, making significant contributions to his fields of study. He, also, had mental health issues. However, it didn’t take a genius to notice the similarities between the two…

Bobby first learnt how to play chess at the age of 6 with his half sister Joan. Their mother, Regina Pustan, was probably a genius as well - reportedly speaking 7-8 languages, the doctor and activist showed great intellect from a young age. Nonetheless, she didn’t have time to play chess with her son and once Joan lost interest in it, Bobby was left to play many of his first games against himself with the help of a book comprising old chess games.

The early years of Bobby Fischer

Already a regular in New York’s chess clubs by 11, his life was chess. According to many, he was the equivalent of a chess sponge – swallowing books and magazines one after the other, being able to retain almost everything in one sitting. Self-taught, Bobby Fischer quickly crushed US chess, becoming the US Junior Chess champion at 13, in 1956. It was also during that year that Bobby played a game against International Master Donald Byrne, later nominated as “The Game of The Century” due to the astonishing beauty and precision in every move, including a middlegame queen sacrifice that drew chess worldwide attention from the strongest Russian GM’s.

From there onwards, there was no return. At age 14, he became the US champion, the youngest to ever achieve that status, and by the age of 15, he cemented himself as the greatest chess prodigy by becoming the youngest chess Grandmaster in chess history. It was therefore time for him to test his skills against the great Grandmasters of the former USSR.

Bobby Fischer IQ

At the age of 16, in Moscow, Bobby famously demanded to play the then current world chess champion Mikhail Botvinnik, though his request was denied. He later referred to them as “Russian pigs”, stating he didn’t like Russian hospitality and the people themselves. This belief had its roots on pre-agreed draws between Russian players looking to muffle Fischer’s ascendance in tournaments, which didn’t go well with the young prodigy.

Also, during that year, Bobby dropped out of high school as he believed school served him little. Regina, although having a role in introducing Bobby to the world of chess by getting him into chess clubs and tournaments, didn’t see eye to eye with her son – moving out of the apartment to pursue medical training in Washington. Bobby, however, was fine with the situation as he famously stated he doesn’t “…like people in his hair”, while referring to his mother. He was also granted a scholarship due to his chess talent and “astronomically high IQ” – Bobby reportedly took an IQ test at 15, scoring 180 points.

It seems to have been during that time that Bobby Fischer’s mental health slowly started slipping away. From anti-Semitic beliefs to stating that women should not be allowed in chess clubs, the outspoken young prodigy would say it all. By the time he was 19, he gave an interview in which he stated: “All women are weak. They’re stupid compared to men. They shouldn’t play chess, you know. They lose every single game against a man. There isn’t a woman player in the world I can’t give knight-odds to and still beat.”. Granted, Judit Polgar was not alive yet…

US Chess Championships

Back to his chess prowess, during the 1963-1964 year, at age 20, Bobby scored the only perfect score in a US Championship – winning 11 out of the 11 rounds. In fact, from 1966 onwards, Fischer would win every single match or tournament he completed for the rest of his life. During those years, he’d also write articles and give chess lectures all around the world.

In the 1966/1967 US championship, which he had won consecutively since his 14th birthday, he was qualified for the next world championship cycle. However, things took an unexpected turn as tournament organizers failed to change the tournament schedule to accommodate Fischer’s religious constraints, which didn’t allow him to play on the 7th day Sabbath – therefore forfeiting two games in protest and later withdrawing, eliminating himself from the 1969 world chess championship. He was leading the tournament scoring 8½ out of 10 prior to his elimination.

Such situations were common to the chess genius who would often make tournament organizers abide to his requests, no matter how specific they were. When rejected, he would negotiate terms and, if he felt necessary, withdraw from the tournament. The problem with that was the fact that Fischer’s demands were growing in size, making him sit out of the 1969 US championship due to disagreements on the tournament’s format and prize fund.

The Candidates Matches

But the championship in question was not a mere tournament, it was also a zonal qualifier with the top three finishers advancing to the Interzonal – the first phase of the world chess championship cycle. Therefore, Benko and Lombardy, 2 of the top 3 US finishers, voluntarily gave up their spots in the Interzonal in order to give Fischer another shot at the world title. What more proof does one need that Bobby dominated his contemporaries to an extent never seen before?

A few tournaments later, Fischer won the Interzonal held in 1970 with 18½ out of 23, far ahead of the competition, scoring seven consecutive wins. That would put him right in line for the Candidates matches, beginning with Taimanov, guided by Mikhail Botvinnik.

The tale goes that after Taimanov asked Fischer how he came up with the move 12.N1c3 in the second game, he told him that the idea wasn’t his – he had come across it in the Russian monograph by GM Alexander Nikitin in a footnote. Taimanov later recalled: “It’s staggering that I, an expert on the Sicilian, missed this theoretically significant idea by my compatriot, while Fischer uncovered it in a book written in a foreign language”. The Russians, however, suspected of Fischer’s ability to read Russian – a skill he developed as a teenager to improve his chess. Fischer ended up beating Taimanov 6-0, putting an end to Taimanov’s chess career after the URSS threw him out.

Going into the second match of the Candidates, Fischer was now facing Bent Larsen. The chess world didn’t believe Fischer would be able to easily breeze past him, nonetheless, not to the likes of Mikhail Botvinnik and then current world champion Boris Spassky, Fischer pulled the 6-0 feat once again. Upon these accomplishments, Fischer was awarded with the highest match performance rating ever. Garry Kasparov later wrote that no player up until that moment had ever shown a superiority over his contemporary rivals comparable to Fischer’s scores since 1966.

Fischer was now set to face Tigran Petrosian – an extremely strategic player known for squeezing wins out of tiny advantages and making very few mistakes. This time, Bobby won 6½-2½, prompting Botvinnik’s first good remarks on him stating “It’s hard to talk about Fischer’s matches. Since the time he has been playing them, miracles have begun. When Petrosian began making mistakes, Fischer transformed into a genius”. Granted, in July 1972, Fischer’s ELO rating of 2785 was 125 points above the world champion and number 2, Boris Spassky. Their match was inevitable.

World Champion!

Prior to the start of the 1972 world championship, Fischer demanded a $250,000 prize, which was unheard of – equivalent to $1,500,000 in today’s currency. But even that wasn’t enough… He demanded the first rows of chairs removed, a new chessboard and that the organizers changed the venue’s lighting – a request which was complied. But after the first game in which Fischer, in an equal endgame, unnecessarily sacrificed his bishop in a position he ended up losing, he was quick blaming the cameras saying he could hear them.

The organizers ignored Fischer’s request to remove them and thus he didn’t show up for the second game and, prepared to stand his ground, the organizers gave in. From game 3 onwards, Fischer dominated Spassky and won 6½/8 in the next games. Spassky gained control in game 11, but it was the last time Fischer would lose. For the first time in 25 years, the URSS got beaten in the world championship – and Fischer got his praise televised in Times Square, but it was a short-lived destiny.

Turning down millions of dollars in sponsorship offers, he locked himself away. Living as a recluse, Fischer got stripped of his title in 1975 after the organizers didn’t meet his list of 179 demands to defend the title. And little was heard from him until 1992 when he defeated Spassky again in an unofficial match, winning $3,350,000 after 20 years of inactivity. He lived in Hungary and then Iceland for the remaining years left due to sanctions from the US that prohibited him from playing that match. Famously, during a media press, Fischer spat on the US sanction stating, “This is my reply”.

The late years and death

Years later, after the 9/11 attacks, Fischer stated that the US got what it deserved because “what comes around, goes around, even to the US”. Fischer was then arrested in Japan for travelling with a revoked US passport and, in 2008, he died from renal failure. Some speculate he suffered from schizophrenia or Asperger’s syndrome, though it is more commonly believed that it was in fact a case of paranoid personality disorder, a disorder he had to live with most of his life.

At the time of his death he was 64 – the number of squares on a chessboard.